Similarly, a need for improved knowledge is indicated by the low frequency of non-literal phrasal verbs among the non-native interpreters, which if translated from production to reception, would mean the risk of non-comprehension when working from B to A. This form of instruction cannot take place in interpreting practice classes, precisely because attention there is perforce directed away from linguistic form; so it should take place in adjunct language support courses. Material for such courses has been uncovered in the current study, where analysis of the KWIC concordances revealed a number of longer multiword formulae (phrasal verbs +…) useful for interpreted language. Some of the concordances have already been converted into learning materials and used with trainees at the Department of Interpreting and Translation (University of Bologna at Forlì). The hope is that such work will continue, and that our understanding of the role of formulaic language in the process and product of interpreted English can be extended by the development of corpus research methods.

This should include more representation in corpora of conference interpreting, to take its place alongside existing corpora of interpretation of parliamentary debates. Work also needs to be done on developing larger corpora of non-native interpreters. The small size of the non-native interpreted language corpus used in this research has meant that the findings presented here must be qualified as merely tentative. The inclusion of different subject matter, forming a larger sample, might have revealed more occasions when opportunities were taken up by interpreters for the choice of phrasal verbs in translations. Finding number 1, that there was a reasonably high frequency of phrasal verbs in INT-A, should also be received with a degree of caution, due to the low proportion of conference interpreting and the preponderance in the data of parliamentary debates. The data on literal, idiomatic/figurative and aspectual phrasal verbs in INT-A and INT-B is summarised in Table 4.

The verbs listed by name in the Table are the most frequent in each category. An asterisk indicates that the verb is neither present in Gardner and Davies' BNC top 100 nor has a BYU-BNC frequency high enough to be included in it, in other words a frequency of 4.23 per million, that of Gardner and Davies' hundredth ranked item. The data confirmed Hypothesis 5, which predicted that non-native interpreters working towards English as their B language would use idiomatic and figurative phrasal verbs less than do native and native-like interpreters.

In INT-A, there were 2200 figurative/idiomatic phrasal verb tokens per million words, while in INT-B there were only 1200 tokens per 1000 words. These data reinforce the theory that processing difficulties make idiomatic and figurative phrasal verbs difficult to access for non-native interpreters working towards B. It should be stated here that most writers on phrasal verbs, and on idiomaticity in general, do not distinguish between idiomatic meaning and figurative meaning.

In Grant and Bauer's view there are three categories of "idiomatic" meaning – first, core idioms, which are completely non-compositional, second, phrasal items with one element that is non-compositional, and third, figurative language. But it appears from Siyanova-Chanturia and Martinez , who review the literature on processing of non-literal phrases, that in this field of research, the three categories are usually conflated. Hence in the context of the current research on interpreted language with its concomitant processing constraints, I will refer to "idiomatic and figurative" phrasal verbs.

In particular, phrasal verb lemmas with idiomatic and figurative meanings were very much less frequent in the language of the A into B interpreters, as were phrasal verbs with aspectual meaning. Despite this, metafunctional analysis showed that the A into B interpreters did use phrasal verbs with interpersonal function, to pursue the role of interpreter as mediator. In short, phrasal verbs are clearly an important resource for SI and the lack of them in the language of A into B interpreters suggests an urgent instructional need.

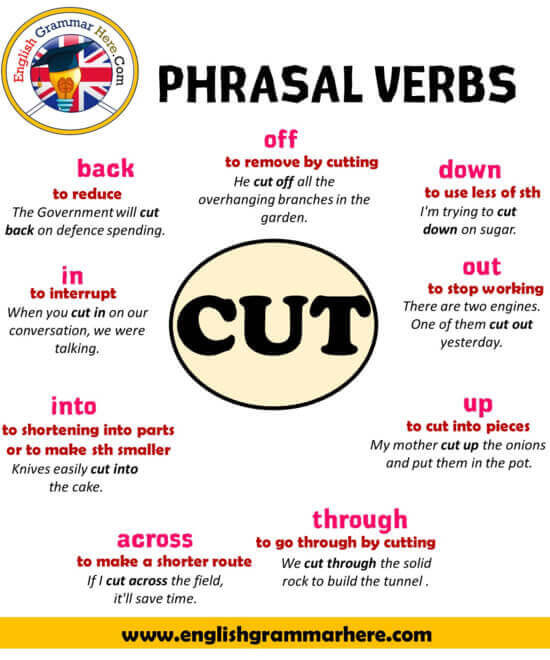

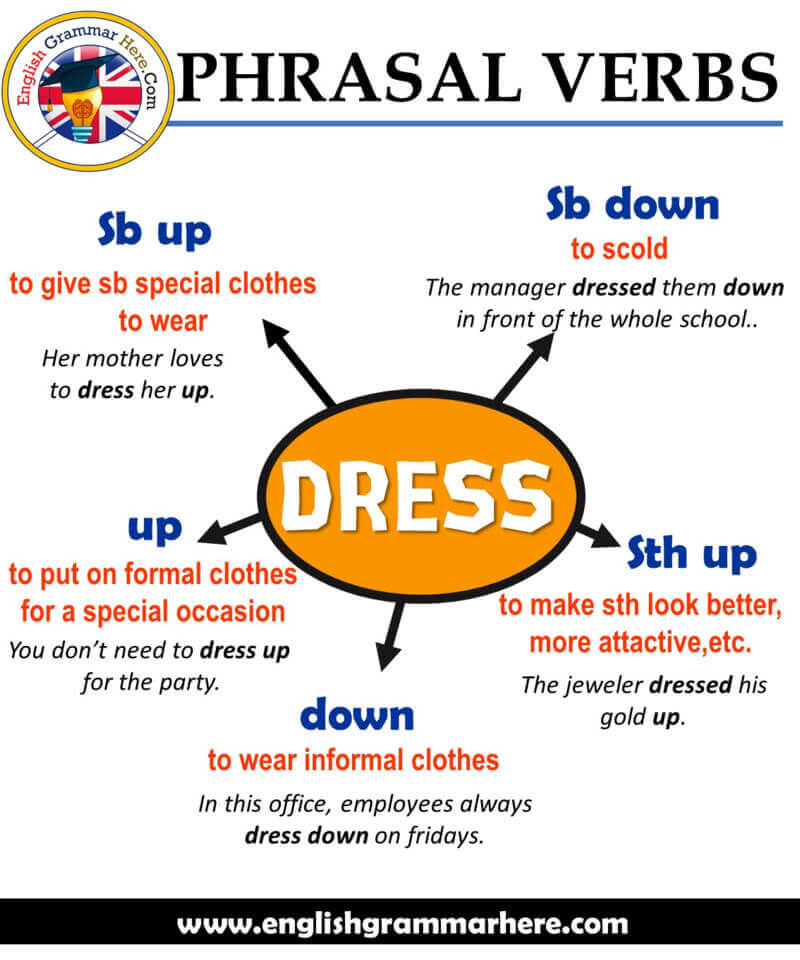

Verb + preposition When the element is a preposition, it is the head of a full prepositional phrase and the phrasal verb is thus prepositional. These phrasal verbs can also be thought of as transitive and non-separable; the complement follows the phrasal verb.a. – after is a preposition that introduces the prepositional phrase after the kids.b. – on is a preposition that introduces the prepositional phrase on nobody.c. – into is a preposition that introduces the prepositional phrase into an old friend.d. – after is a preposition that introduces the prepositional phrase after her mother.e.

– for is a preposition that introduces the prepositional phrase for a linguist.f. – by is a preposition that introduces the prepositional phrase by your friendVerb + particle When the element is a particle, it cannot be construed as a preposition, but rather is a particle because it does not take a complement. These verbs can be transitive or intransitive. If they are transitive, they are separable.a. – up is a particle, not a preposition.b. – over is a particle, not a preposition.c.

– down is a particle, not a preposition.d. – in is a particle, not a preposition.e. – out is a particle, not a preposition.f. – in is a particle, not a preposition.Verb + particle + preposition (particle-prepositional verbs)Many phrasal verbs combine a particle and a preposition.

Just as for prepositional verbs, particle-prepositional verbs are not separable.a. – up is a particle and with is a preposition.b. – forward is a particle and to is a preposition.c. The other tanks were bearing down on my Panther. – down is a particle and on is a preposition.d.

They were really teeing off on me. – off is a particle and on is a preposition.e. – up is a particle and on is a prepositionf. Susan has been sitting in for me. – in is a particle and for is a preposition. (They looked them over carefully.)look upsearch in a listYou've misspelled this word again. She picked out the guy she thought had stolen her purse.pick uplift something off something elseThe crane picked up the entire house.

(Watch them pick it up.)point outcall attention toAs we drove through Paris, Francoise pointed out the major historical sites.put awaysave or storeWe put away money for our retirement. She put away the cereal boxes.put offpostponeWe asked the boss to put off the meeting until tomorrow. (Please put it off for another day.)put onput clothing on the bodyI put on a sweater and a jacket. (I put them on quickly.)put outextinguishThe firefighters put out the house fire before it could spread.

(They put it out quickly.)read overperuseI read over the homework, but couldn't make any sense of it.set upto arrange, beginMy wife set up the living room exactly the way she wanted it. She set it up.take downmake a written noteThese are your instructions. Write them down before you forget.take offremove clothingIt was so hot that I had to take off my shirt.talk overdiscussWe have serious problems here. Let's talk them over like adults.throw awaydiscardThat's a lot of money!

Don't just throw it away.try onput clothing on to see if it fitsShe tried on fifteen dresses before she found one she liked.try outtestI tried out four cars before I could find one that pleased me.turn downlower volumeYour radio is driving me crazy! It really turned me off.turn onswitch on the electricityTurn on the CD player so we can dance.use upexhaust, use completelyThe gang members used up all the money and went out to rob some more banks. This suggests that access to individual figurative/idiomatic phrasal verbs during B-direction interpreting is likely only if frequent experience has brought them relatively near to the surface of memory.

Conversely, the finding that figurative meanings of phrasal verbs less frequent than the 4.23 per million threshold are hardly used at all by the B-direction interpreters (only a single occurrence of spring up – see Table 4) has a plausible explanation. It is likely that, given the time lag shown in the literature for NNS access to non-literal items, less frequent phrasal verbs take too long for the non-native to access in the SI situation. There is for example the phrasal-prepositional verb come up with, which occurred as many as fifteen times, thus contributing to this verb's position as number ten for keyness in INT-A . Come up with collocated relatively frequently with proposal . This distinction is subject to the qualification that some aspects of ideational metafunction, such as some mental processes or some material processes, are likely to recur in repeated contexts and are likely to prove productive.

It is worth commenting on Darwin and Gray's phrase 'not commonly understood', for if a non-native speaker is unaware of the aspectual meaning of particles, aspectual phrasal verbs become in effect non-compositional. On the other hand, in the examples quoted by Darwin and Gray , for comprehension purposes the aspectual particle does not need to be understood as the meaning is easily recoverable in the context from the lexical verbs ate and drank. In these examples the potential problems for non-native speakers deriving from lack of knowledge of the aspectual meaning of up would lie in production, in the inability to produce the pragmatic effect of completion. For phrasal verbs used with interpersonal metafunction, the situation was reversed.

The non-native interpreters used phrasal verbs interpersonally more often than the native speaker interpreters, so that Hypothesis 4 was not confirmed. However this cannot reliably be checked, since there was no information of this type in 2249, which formed a substantial component of INT-A. An alternative explanation is that the non-native interpreters have substantial experience of phrasal verbs used interpersonally, as a result of having passed through courses of English language conducted using communicative language teaching methods.

Therefore the assumption that phrasal verbs would be hard to access for non-native interpreters during SI does not apply in the case of interpersonal contexts. If the meaning was entirely literal, they were classified as literal. With aspectual phrasal verbs, if figurative/idiomatic they were classified as figurative/idiomatic, and were classified as aspectual only if the meaning of the verb was literal, with aspectual use of the particle. The final test for literal meaning was any of the meanings of the individual word listed in a contemporary dictionary , according to Grant and Bauer's method as outlined in section 3.2 above. To help ensure plausibility of the classification, the analysis was repeated after a month's interval, with an index of agreement of 0.97. Each of the following sentences uses a phrasal verb.

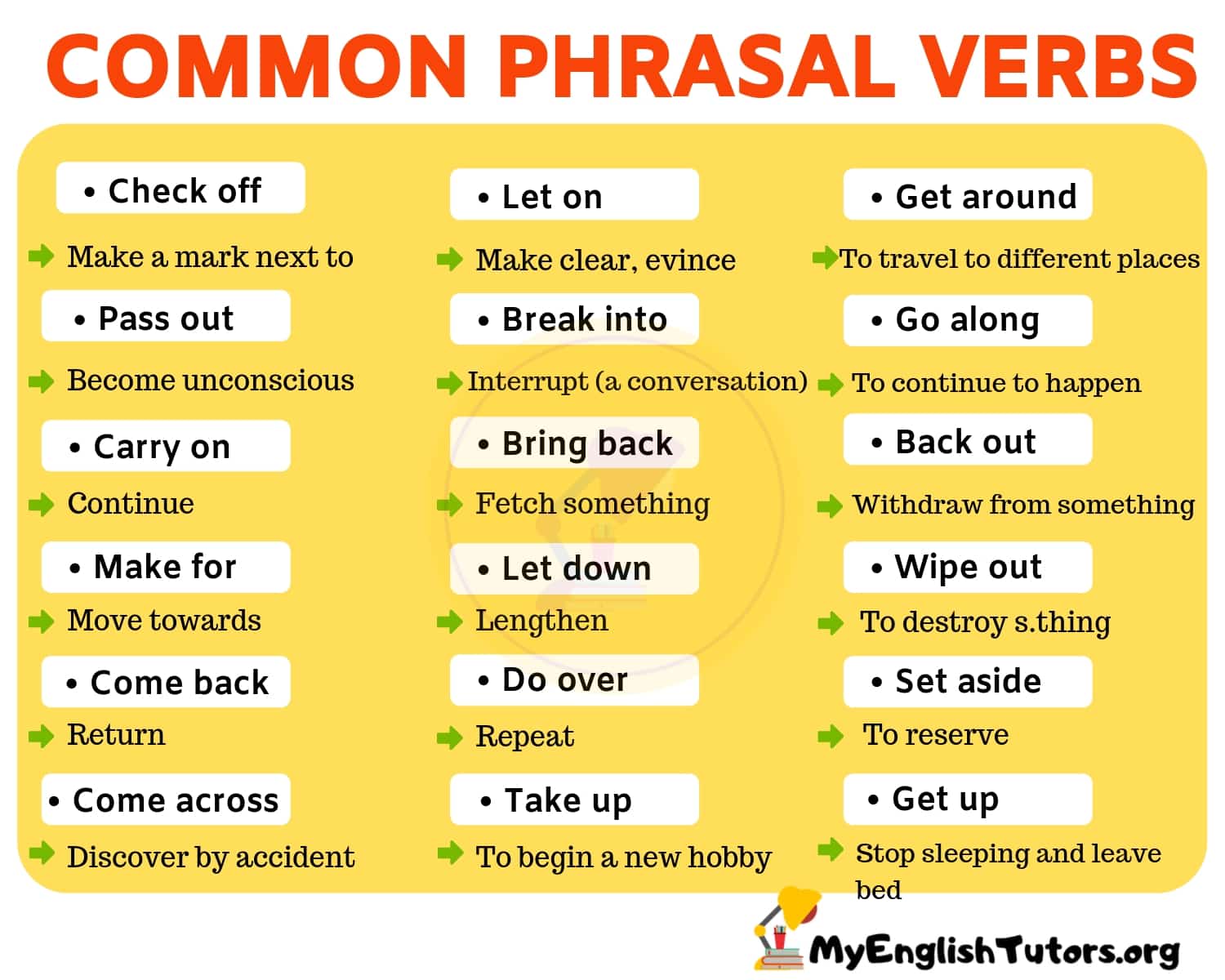

Read each sentence carefully and figure out exactly what the sentence is trying to say. Often, phrasal verbs have different meanings than a verb being modified by adverbs or prepositional phrases. You may also notice that some of these phrasal verbs can be separated out and the sentence will still make sense. At the same time, some particles can be separated from the verb so that a noun and pronoun can be inserted, whereas other particles cannot be separated from the verb; in addition, still others can be used in a separated form or as a unit.

Moreover, phrasal verbs can be intransitive -- not followed by a direct object – or transitive – followed by a direct object. Therefore, phrasal verbs can be separable, inseparable, transitive or intransitive . The ideational metafunction, by virtue of its application to content, can be stated to cover interpreted product. Phrasal verbs used for the ideational function in INT-A cover a wide range of types of meaning.

As indicated above, some phrasal verbs used with ideational meaning are likely to recur whatever the subject matter being translated, such as certain mental process verbs, while others will be linked with a more restricted, specialised context. The discussion is organised according to verb types – mental processes, material processes, and relational processes. The degree of productive value for interpreters of certain phrasal verbs, and of the multiword expressions of which they form part, as revealed by the corpora, is discussed within these sections.

Of course verbs cannot intrinsically be placed in a single one of the three categories of mental, material and relational processes. I classified them as belonging to one of the three categories on the basis of the type of meaning that they predominantly expressed in each single instance of use in context actually observed in the KWIC concordance. This study investigates the hitherto understudied area of the use of phrasal verbs in expert academic writing in the discipline of Linguistics. Using a specifically designed corpus of L1 English academic expert writing in Linguistics, we investigate the frequency and meanings of PVs in this sample. Contrary to previous findings, our results indicate that PVs form a large proportion of verbs identified in expert writing. An analysis of meanings of the most frequent phrasal verbs in the corpus indicates that in academic writing PVs are used in restricted and sometimes metaphorical senses which are less common in general language use.

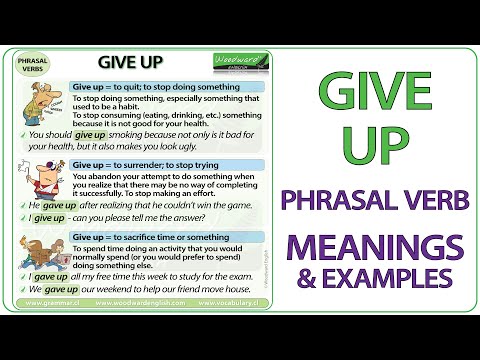

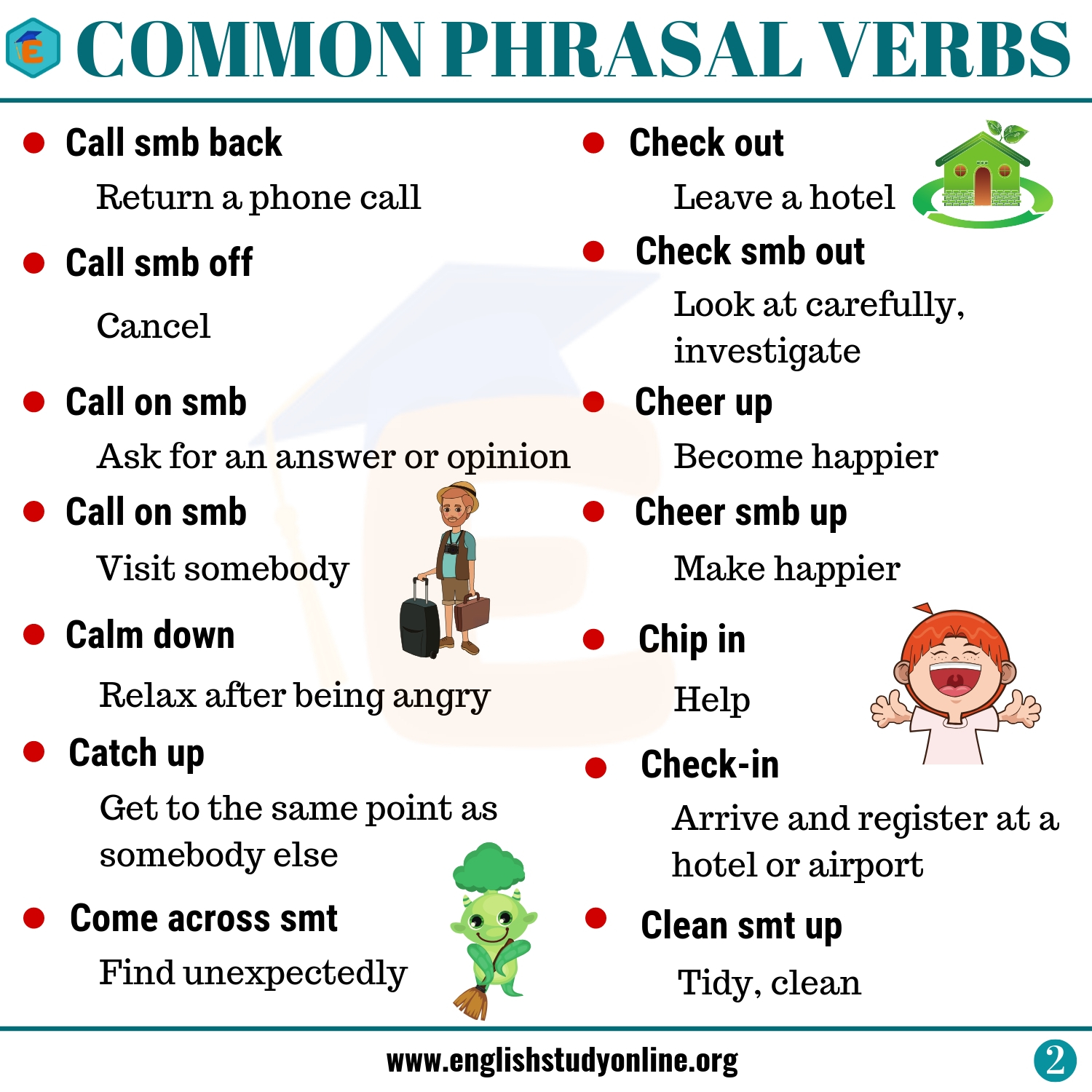

We conclude our study by suggesting some recommendations for introducing phrasal verbs into the teaching repertoire of English for Academic Purposes. For many students, one of the most difficult parts of learning English is studying phrasal verbs. A phrasal verb is a verb that is combined with an adverb or preposition.

The combination creates a new meaning, often one that is not related to the definition of the base verb and is difficult to guess. Table 3 shows that there was a substantial representation of all three metafunctions in the INT-A corpus. In the INT-B corpus, all three metafunctions were represented, but the proportion of phrasal verb tokens used for textual metafunction was lower than in INT-A. The data therefore confirmed Hypothesis 3, thus in turn confirming that native and nativelike interpreters use phrasal verbs as a resource to textualise their interpretations. To operationalise these hypotheses, the frequencies of phrasal verbs were measured in two corpora.

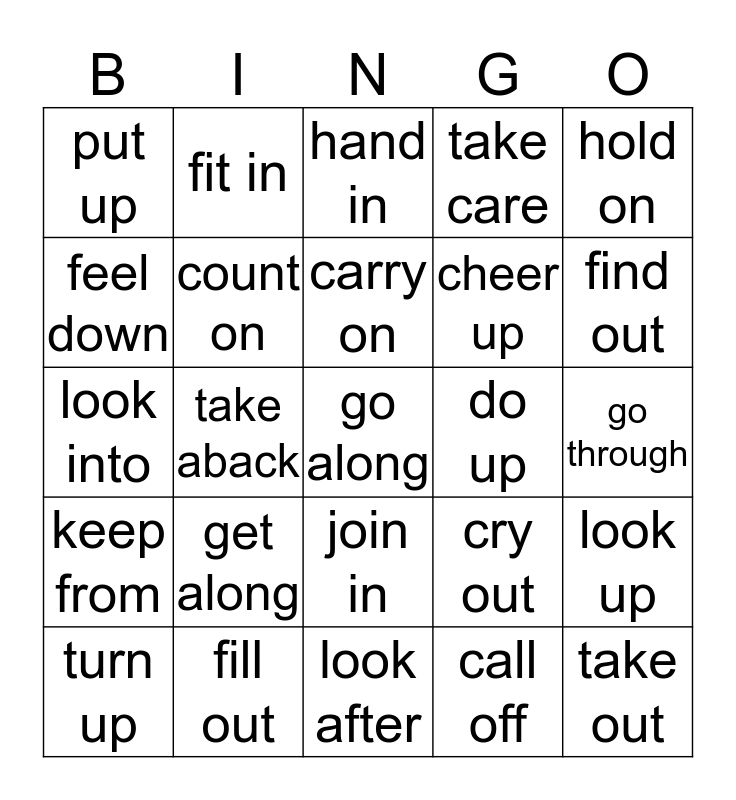

Hypothesis 1 was tested by measuring the frequency of phrasal verbs in a corpus of English language interpretations produced by interpreters of native-speaker standard, which was called INT-A. Hypothesis 2 was tested by measuring the frequency of phrasal verbs in a corpus of English language interpretations produced by non-native interpreters, which was called INT-B. The notions of "reasonably frequent" and "reasonably frequently" were operationalised by comparison with frequency in the language as a whole, as represented by the BNC. Students may use the phrasal verbs incorrectly in their sentences during this part of the exercise.

However, later in the exercise they will be able to correct their sentences. The goal at this step is for students to inductively learn the meanings of the phrasal verbs. In an inductive learning approach, students use examples to guess and come to learn the rules of grammar or word meanings. Phrasal verbs used for the textual metafunction were much less common in INT-B. However, the two most key phrasal verbs in INT-B were used with textual metafunction. These were move on, signalling the presentation relation, and sum up, used to indicate a relation of summary.

It is thus clear that textualisation of output was taking place explicitly in INT-B, as one would expect. The meaning of "reasonably frequently" is clarified in the next paragraph. Although phrasal verbs are acceptable in spoken English, they are frequently considered too informal for academic writing.

Is Go Up A Phrasal Verb Furthermore, phrasal verbs often have multiple meanings. Your aim is to write your paper in a simple language that makes your work clear and concise. It is therefore recommended that you replace phrasal verbs with formal one-word alternatives. The two categories have different values. Particle-verb compounds in English are of ancient development, and are common to all Germanic languages, as well as to Indo-European languages in general. Those such as onset tend to retain older uses of the particles; in Old English on/an had a wider domain, which included areas now covered by at and in in English.

Some such compound nouns have a corresponding phrasal verb but some do not, partly because of historical developments. The modern English verb+particle complex set on exists, but it means "start to attack" . Verb-particle compounds are a more modern development in English, and focus more on the action expressed by the compound. That is to say, they are more overtly verbal. A complex aspect of phrasal verbs concerns the distinction between prepositional verbs and particle verbs that are transitive . Particle verbs that are transitive allow some variability in word order, depending on the relative weight of the constituents involved.

Shifting often occurs when the object is very light, e.g. Phrasal verb.1 She looked his address up. Phrasal verb.2 When he heard the crash, he looked up. Not a phrasal verb.2 When he heard the crash, he looked up at the sky.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.